Engaging children, young people and parent/carers in a Framework for Ethical and Effective Information Use

Engaging children, young people and parent/carers in a Framework for Ethical and Effective Information Use

Sarah Gorin

Sarah Gorin is a Senior Research Fellow at the Rees Centre and has recently joined the Children’s Information Project (CIP). Sarah has worked in Children’s Social Care and Special Educational Needs and Disabilities research for over 25 years and previously worked at the University of Southampton exploring parents’ views on linking data and predictive data analytics.

As I started my new role, I was telling family and friends about the research I will be doing to engage children, young people and parent/carers in a consultation about the Framework for Ethical and Effective Information Use recently published by the CIP.

No sooner than I said the words ‘information’ and ‘data’, I sensed their eyes glazing over! Whether we like it, or not, we are increasingly living in a world in which our personal information is being used in a multitude of ways, including by public services, such as children’s social care. Many people (and I’ve been guilty too!) may actively choose not to engage too deeply with thinking about where our personal information goes, what is done with it and what the impact of this may be.

I have been thinking about why this is and what this means for designing a consultation with families that will be engaging and meaningful for them.

What impacts people’s views about information use?

In thinking about my previous research at the University of Southampton on parents’ views about information use, I had the following reflections:

1. The extent to which we connect provision of personal information with the services that are provided to us is mediated by our individual background and experiences;

As a parent or a child/young person, when we want to access a service, we are looking for our needs to be met appropriately, in a timely and considerate manner. If we are seeking support, for example from our GP, the immediate need for this support is likely to be paramount.

We will be asked for personal information to help us to access that service. In this transaction, we may not connect what information is being collected about us, why and how it might be shared (and the extent to which our voice is clearly articulated in that information) with the service we receive. We also may not feel we have a choice about giving our personal information, or a voice about how information about us is used.

Conversely, if for example, we are in contact with safeguarding services, the police, or are from a minoritised group and we already feel under surveillance, we are more likely to think about what information is being collected about us and how it might be used.

2. Our background and experiences also shape our level of trust in services to collect and use our information ethically and effectively;

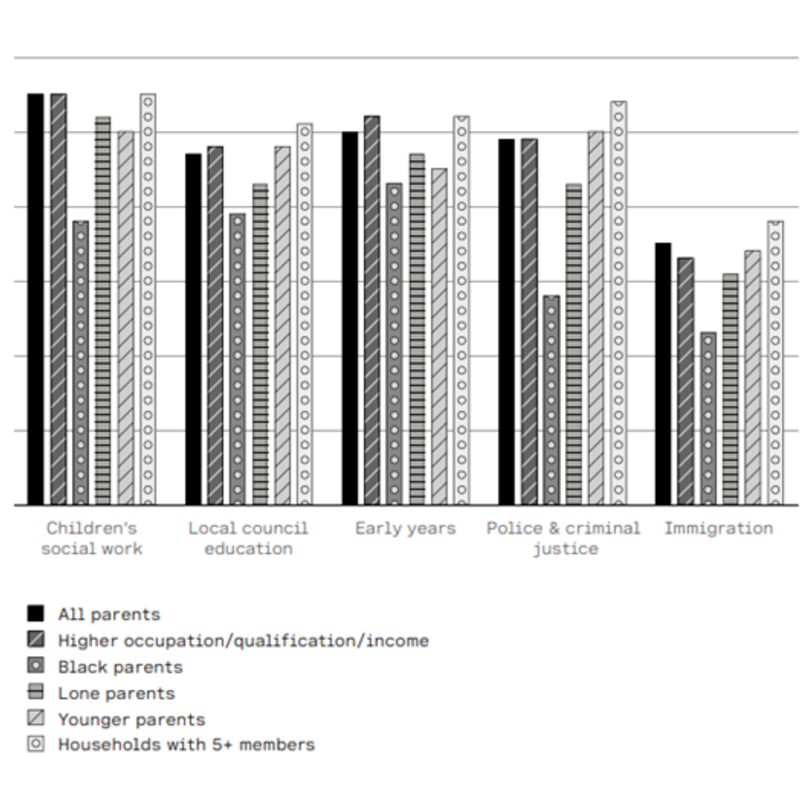

In a nationally representative survey of parents undertaken as part of our previous research, trust in the management of personal records varied according to the service type and was highest amongst those in higher occupation, qualification and income categories and lower amongst lone parents and Black parents (Edwards et al, 2022).

3. Many parents, young people and children do not know or understand the ways their personal information can be used by public services;

Technological developments using people’s information are evolving at a much faster rate, than public knowledge and understanding of them. In the survey of parents, we found that the majority (72%) knew digital records were collected and stored by public services, but far fewer knew that digital records from different sources can be joined together to find out more about individual families (53%) (Edwards et al, 2021).

In our focus groups with parents, there was little knowledge and understanding of the use of predictive analytics in children’s social care (and more broadly) and very few parents understood how predictive analytics can perpetuate bias and discrimination (see University of Bristol and University of Southampton for more explanation).

This is not surprising. It can be very hard to find out how your information is being used. Whilst information use should be covered by privacy notices on websites, the information is variable, can be difficult to locate and to understand. As researchers, using a Freedom of Information Request we struggled to find out about where predictive analytics was being used in local authorities (Gillies et al, 2022).

There is no national register for public services who are using predictive data analytic systems, so there is limited information about who is using it and what data is being put into these systems. The use of private companies to manage local authority data can also be hard to find out about.

4. There are thorny issues around use of personal information and children, young people and parents may feel powerless to have an influence;

Parents in our research raised fundamental questions about ethics, rights, power, consent and accountability (see Gorin et al, 2024). There were often no easy answers;

- There were different views about whether information about children held by services such as health, social care and education should be joined together, i.e. with a Single Unique Identifier. Parents of children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities were supportive of the Identifier, because they wanted smoother service access and to minimise re-telling their stories, but parents who had negative experiences with social care services were less likely to be supportive.

- Inaccurate recording led to lack of trust in public services and could have negative implications for parents – one parent was investigated by child protection following a mistake on records that showed health appointments that had been cancelled by the hospital, as missed;

- Inappropriate sharing of information could have immediate implications, e.g when a parent’s address information was inappropriately shared in a situation of domestic violence;

- Protracted processes for Subject Access Requests and provision of partial accounts with large amounts of information redacted meant it was hard for parents to hold local authorities to account;

- Children’s records were not always written in a humane or appropriate language;

- Consent did not always feel meaningful to parents e.g. with Child in Need services because they did not feel they had a choice about providing personal information;

- Child protection investigations and red flags left on social care records following unsubstantiated claims of abuse, led to stigma and discriminatory experiences of public services. This could discourage use of support services in the future.

Why does this matter?

When I reflect on these findings, it seems clear how important it is that we do talk to families because personal information belongs to them. Public services are custodians of families’ data – as such, not only do families have the right to be heard, but they also have critical insights that can challenge current practices and through working with families we can develop more ethical information systems.

To engage families, it is important we give them the information they need to help clarify what can happen to their information so they can make informed choices.

Sometimes we need to prioritise talking about difficult things – because often the hardest things to talk about are the things that matter the most.

If you work with parents and/or children and young people and you think they would like to be involved in the consultation, please do get in contact with me at sarah.gorin@education.ox.ac.uk

If you work for a local authority or public service and would like to know more about the Children's Information Project framework for ethical and effective information use and hear from organisations sharing practical examples and perspectives on how this can be achieved, please join our webinar on 4 March. Register your interest here.

To find out more about the Children’s Information Project, sign up for the CIP newsletter.